Discovering Walter Keller and Lucy Stone Terrill

(2025 ancestral memoir)

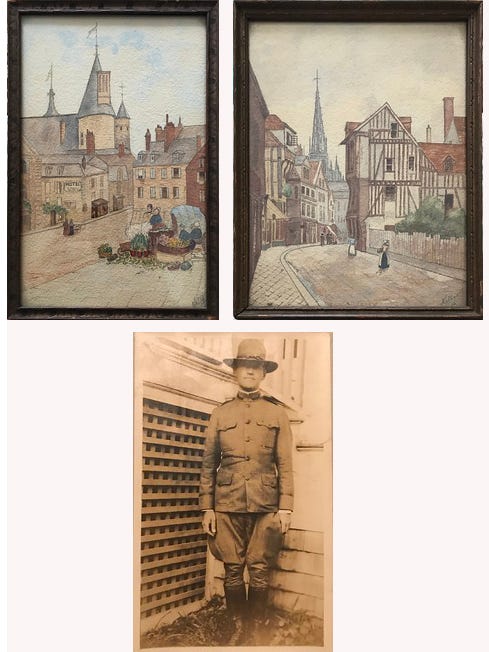

In a series of different homes where she lived, my mother Lucy Mallan displayed a trio of postcard-sized framed pictures she had inherited from her grandmother. Two were watercolors (2nd) of idyllic Alsatian village scenes dated 1915, and the third was a 1917 photo of the painter, in his American military uniform, not long before he shipped out to France to fight in WWI. This was the only photo of anyone in uniform among my mom’s family, and always stood out, especially in juxtaposition with the lovely little paintings she always hung it with.

Like the ‘trench art’ popularized after the first world war, the paintings were made more powerful by knowing the artist was a soldier: the one in the photo. They seemed like fragments of beauty somehow eked out amid the miserable violence that laid waste to those lost storybook landscapes he painted, as the war wasted the lives of a generation. The grouping of the pictures suggested that somehow before dying the artist had created and mailed home these fragments, in turn becoming the only part of him and his potential that survived.

But this soldier and his art were even more poignant to my mom as he was her grandmother’s brother Walter Keller, killed in France not long after making the watercolors. So he died 15 years before my mother would be born, leaving the family not only heartbroken but forever speculating about what his talent might have produced if he hadn’t been cut down so young. Rippling across the generations was the loss of the relationships he might have had with his niece my grandmother, great-niece my mother, and their sisters.

This narrative of loss captivated Lucy, and me as well, even though I was even further removed, by enough generations that I could not have known him even if he lived into old age. My mom and I were also touched by the thought that Walter’s ‘artist genes’ might be said to have survived, or at least been passed down, through the generations, to the creatives in my generation, and finally to our kids, including my son Santiago, whose artworks Lucy framed and hung next to Walter Keller’s paintings.

This is such a satisfyingly sad full-circle tale in its way that for years I was unaware of key elements that dramatically enrich but also change the story. Those recently discovered puzzle pieces came from an equally surprising source: researchers in San Diego who unbeknownst to the family spent years studying my great great uncle Walter Keller–as well as his wife (and therefore my great-great-aunt), Lucy Stone Terrill, after whom Lucy may even have been named. Those scholars and their studies revealed more to me about the couple in the past couple years than our own family had known, let alone handed down, during the century since we lost Walter in the Great War.

My interest in Walter had been growing since I moved to Europe in 2019 and began periodically driving past battlefield cemeteries full of American soldiers from the world wars. It occurred to me for the first time that I might be able to visit Walter Keller’s grave, and perhaps I should, especially when I realized he had fallen just a few hours’ drive from where I live in Brussels: at the battle of St. Mihiel. I discovered this, though it may reinforce my status as an aging gen-X cliché, through Ancestry.com, a hobbyist family-tree building app, to which my wife had given me a subscription as a 50th birthday present.

As I learned to read between the lines of some of the drier documents I found online, I looked at Walter Keller’s dates, Nov 22 1881- Sept 17, 1918 and was hit by a couple things I’d missed though they had been staring me in the face. First: that he died just two months before the armistice, begging the question of whether his death was needful or more akin to the people killed at the literal last minute of the war, in painfully ironic timing which never fail to make the sacrifices seem even more pointless. Second, perhaps more shockingly, he was thirty-six years old!

This last realization sent me back to the photo and others from the summer of 1917 when he enlisted. I realized I was looking at an older man than the teenage doughboy I’d imagined crouching (and painting) in a trench. He was handsome, with intelligent eyes and a warm expression. His siblings were all grown up as well–here’s a photo of them with their mother at what was likely a farewell gathering–given that Walter was already in uniform–including his sister, my great-grandmother Florence, who was raising her three little girls with my great grandfather Laurence Tanzer.

Walter had gone to France, and died, as a Captain in the Corps of Engineers. This checked out, as I learned he had been an engineer in the US, presumably with a full professional education before going off to war. So he was twice the age of the lost generation who enlisted as teenagers, and hardly typical cannon fodder: as an officer he should have been more out of harm’s way, and as an engineer even less likely to be in the trenches–except to build them, along with the roads and bridges that carried soldiers to them.

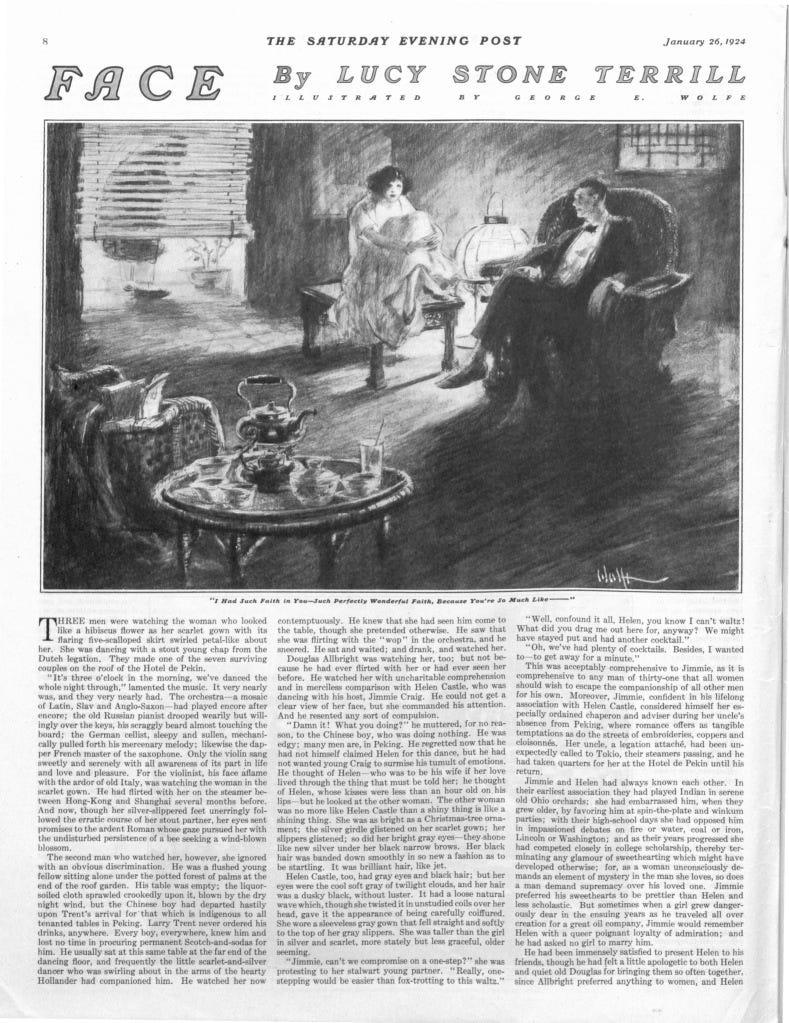

Still it seemed courageous to have joined up voluntarily when he had a settled life back home: a degree, a career and as I learned: a wife, Lucy Stone Terrill, 9 years younger at 27, whom he had married only three years earlier in 1914. Although 27 may sound young, many women of her generation were married with children by the time she met Walter. But she was no spinster; rather she was an adventurous individualist herself: a ranch owner, a teacher, and above all a successful author of widely published and popular short stories, at least one of which became a film. In this way, along with discovering a lost uncle, this line of research had gained me a truly fascinating new aunt I had never heard of.

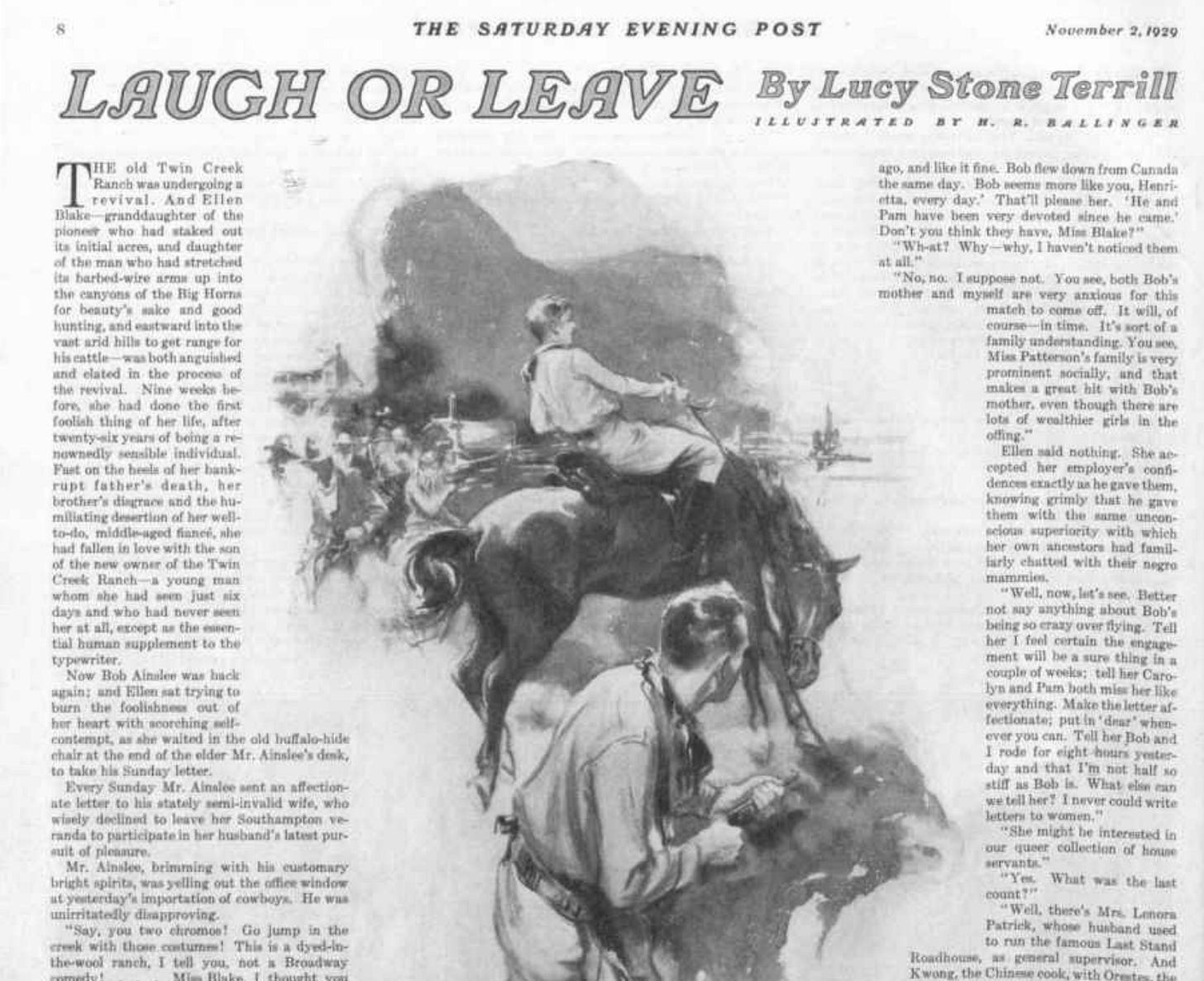

I would learn so much more about Lucy Stone Terrill but the initial web search revealed one short story she had written in 1924 for the Saturday Evening Post, entitled Face, about the widow of an American WW1 veteran who encounters one of her late husband’s comrades when both are in Shanghai. I wondered to what extent this was autobiographical, kept googling, and found a reference to Lucy and this story in a 2012 study of war widows that told the true story of her traveling to France in the aftermath of Walter’s death to work with his company as a YWCA volunteer.

Having pieced these surprising facts together by Fall of 2022, it seemed like time to visit Walter’s grave.

I had visited American war cemeteries before, such as those in Normandy, but only as a touristic/historic must-see. I had had a taste of the quasi-religious rituals the military has built up around these places when I watched my dad inurned at Arlington with such pomp as the folding and presenting of the flag to my mom by a ceremonial guard and unsolicited attendance of a couple ‘Arlington Ladies,’ plus a chaplain of some kind. We’re just not a military family, nor are we a religious one, so all the rites just made it more impersonal, i.e. less specific to my father. We’re not very good at patriotism or solemnity of any kind, to be honest. My mother and I weren’t exactly laughing during the burial ritual, but she certainly raised an eyebrow at me that indicated what we were both thinking: what an awkward fit Arlington Cemetery is for the person John Mallan really was. On the other hand it was of relatively little ecological impact and free of charge, as was Lucy’s inurnment by his side after her death in 2021, which might be a better explanation of why both of them chose it. Truth is, neither placed much more significance in a person’s final resting place than they gave credence to the afterlife.

My dissociation at my dad’s inurnment came from knowing him better than the people now caring for his grave; pulling up to the American cemetery at St. Mihiel the odd feeling was rooted in not having known Walter at all, not having heard of him in family lore, and having little idea of what he might have thought of it all. I imagined we might be in and out of the cemetery fairly quickly, given that I felt hardly more connection to the buried soldiers there than an average American tourist, albeit with a little recent reading under my belt on the absurd catastrophe of WWI.

I decided to bring prints of Walter’s watercolors and photo, along with info (complete with links) about Lucy and Face, all of which I put on small cards, then laminated them with a plan to leave them at his grave that day. In that way I suppose I was trying to build a more personalized bridge across the century from his current gravesite in France back to who he was in life.

We took a photo of me outside the gate which I later thought bore a resemblance to the awkward full-body photo we have of Walter in uniform: not only the stance but the rounded face he must have gotten from his Dad’s side as I suppose I did from mine. We then entered the cemetery, and that’s when things got weird. We noticed a crowd forming for an event of some kind, and as we avoided that group and walked toward the office in hopes of getting a map of the gravesites, a staff member rushed out to greet us.

This was Joseph Alotto, the Superintendent of the Cemetery, who acted for all the world as if we were expected, projecting the compassionate warmth of a funeral director speaking to the family of the recently-departed, rather than a middle-aged great-great nephew over a century after the burial. He did acknowledge that it wasn’t every day that any of the fallen soldiers’ actual kin came by any more, but he made clear there was a protocol he’d like to take us through. He brought us to the office and gave our ‘loved one’s’ name to Marie-Lou Meyer-Vinot, one of the remarkably understanding and knowledgeable staff waiting in the visitor’s center for just such a visit. (I dearly hope they are all still there, in the wake of the Doge cuts earlier this year). We thanked the Superintendent, told him we could take it from here and understood he was busy with the growing crowd of visitors–was that a normal daily occurrence? He assured us that those other guests could wait: there was nothing more important to him than to assist in our visit, so he would give us time to walk the grounds and we agreed to meet him at Walter’s gravesite.

In the office we met another American couple, who told us they were Air Force people based at Ramstein, Germany, meaning that like us, they had driven a few hours to see the graveyard. They were not related to anyone buried here but explained they had ‘done’ a number of Europe’s American cemeteries, and had determined this one was next on their list. I asked if they spent a lot of their long weekends honoring the fallen in this way, and they laughed and said ‘no, only Veterans’s Days and Memorial Days!’

Yes, by then it was clear that the crowd–mostly French people, ages 8-80--had gathered for special events connected to the date: 11 November, which we call Veterans’ day and have tied to all veterans, but which the Europeans still call Armistice Day, on which they specifically reflect on the sacrifices and lessons of World War One. As school teachers, of course, we see it first-and-foremost as a 3-day weekend that our bosses only sometimes choose to give us off, when the 11th falls close enough to a weekend. More than for any other reason, we were at the cemetery that day because the 11th was a Friday.

In part because I’m American and a post-Vietnam one at that, I’ve never regarded WWI as offering any lessons, or at least none that ennobled anybody: none that even stuck long enough to prevent another war gearing up between much the same nations, in less than a generation– and after the first was supposed to end all wars. Some of the memorials around Europe, such as the one at Ypres, Belgium where the Brits were dealt a horrific massacre, make explicit reference to the hope that the monuments will be a reminder to strive for peace. To my eyes and ears the ocean of stone crosses surrounding us at St. Mihiel seemed less to be saying ‘what a noble sacrifice’ and more ‘what a bloody waste.’

Seeing my uncle’s own cross (yes, it’s a cross) did little to counter that message. His dates (1881-1918) did frame a longer life than most of the boys killed and buried here, but still it seemed his life was cut short for nothing. How much more life could he have lived, as an artist, an engineer, a husband and perhaps a father, an uncle to my grandmother, aunts and mother? I leaned the laminated postcards against the base of the white stone cross, sticking out of the manicured, somewhat sodden grass. I doubted the maintenance crew would let this type of paraphernalia stay for very long after we left. I looked around at the monumental architecture, most of it erected in the 30s, with clean deco lines that, combined with the eagle and hero imagery, was as reminiscent of 20th century fascism as anything, but in fact predated the Nazis’ rise by a year or two. I hoped reuniting Walter with his delicate watercolors even for a few minutes might be more his speed than all this stoney hero worship.

Joseph Alotto approached with two little flags sticking out of...a plastic pail of brownish sand. He explained the sand was for a special kind of ritual they do, just for visiting family members. A little like if it were Holy Land soil kept in a church reliquary, this sand was specially trucked here from Normandy–you guessed it, from Omaha Beach where Americans had needed to invade all over again, just 25 years after Walter died, to re-liberate Europe and put another end to another endless war.

The Superintendent acknowledged with a self-effacing chuckle that the Omaha sand made more sense when used at WWII cemeteries, but he hoped we still might find solace in the mini ceremony that followed. Basically, since the crosses are white marble, they maintain their uniform ghostly white glow in all weather, and even in the recessed carved lettering. By rubbing wet brown sand into the letters, you can make the name pop in contrast, and stick out among the other crosses, at least until the next rainstorm: by design, a poetically ephemeral ritual but immersive and unforgettable, as evidenced by this memoir.

I was to learn that I was not the first family member to visit the grave. His widow had volunteered in France and spent time with his comrades just after the war was over; she may well have seen the muddy battlefield even before it was converted. And Walter’s sister, my great-grandmother Florence Keller Tanzer had visited around 1920, when there were rows of well labeled crosses–made of wood–and little else. From her photos (discovered in a photo album kept at Alice Belgray’s that Florence seems to have compiled in the same era) you can also see that she bought a potted flowering plant and seems to have planted it near the cross.

Along with the fact that the wood crosses Florence photographed were replaced with stone ones, and buildings, plants, statues and roads were added, the photos show that the cemetery’s 1920 layout was even different in the relative distance of the crosses. I suppose this begs the question of whether any of the markers are really above the graves of the correct remains–which would have required them to meticulously move the bodies at least once to make the cemetery. All a little morbid I know, but given that this had first been a battlefield riven with trenches and craters, then a temporary graveyard, then a permanent one, the thought definitely occurs to you of the whole space as a theatre set: sanitizing, glorifying or even seeking to justify its haunting underlying brutality.

I wondered if Florence had been struck by the use of a cross to mark the grave of her brother, given that they were raised as secular Jews, and to my knowledge he never converted to Christianity, though he was married (by a reverend) to what seems to have been a secular Christian woman, whom he’d listed as his next of kin. There have been recent efforts to change the crosses to Stars of David for several WW2 vets, and the Cemetery commission willingly does it upon request. I mentioned to the Superintendent that Walter was Jewish and he very earnestly said I could come fill in a form and they’d change it right away. But I couldn’t be sure if that’s what Walter would have wanted–he was raised quite irreligiously as far as I can tell and his widow would have known best what his wishes would be–so I thanked the Superintendent but said we’d stick with the cross for now.

Meanwhile as I smeared the Norman sand into the engraving (our host kindly gave me the option for him to do the smearing, or for me to get to), and setting aside any skepticism, artificiality and irony, both Trish and I suddenly found ourselves quite moved. Moved not only by the loss of Walter and our little attempt to reclaim him for the family, but also by the kindness of these US government workers caring for his grave. Their compassion and welcome for us was so sincere that it was hard to claim that the place was all pomp and no meaning; in fact the visit proved very meaningful for both of us. The Superintendent gave one last brush of the excess sand from the cross, planted his two little flags–one French, one American– and said he had to get over to the ceremony, which he hoped we’d feel very welcome to join.

We followed him to a colonnade where the crowd had assembled. A French honor guard in reflective chrome helmets marched past the speaker stand, and two wreathes were laid in perfect sync–one by a French dignitary with a tricolor sash (who turned out to be the mayor of St. Mihiel), and one by Marie-Lou from the office. Both national anthems were played, and then the Superintendent read his speech in English, which he explained had been written by Joe Biden: ‘The First Lady and I know first hand the loss of a family member who is a veteran…’ and so on. It even included a pitch for his VA legislation that was current at the time. Pretty much a clunker and went over like a lead balloon with the barely-anglophone crowd of locals. But it was fitting for us since it only added to the surreality of the day.

The Air Force people urged us to stay as they planned to, for the French part-deux of the ceremony. Everybody got in their cars and drove a mile into town to the square that features the permanent WWI memorial–every small town has one, with the names of a dozen or so local casualties. At the memorial, the mayor had her turn to speak, and in perfect contrast to the Biden speech, quoted French poets and philosophers on the subject of peace, and acknowledged the foreign guests, including the cemetery staff and ourselves, whose nation she thanked for its sacrifice of blood and treasure in order to liberate its sister republic, France.

As we got in our car we counted ourselves lucky to have been there for all that, somewhat as if we had caught a local festival that enhanced our travel experience…but also had some time as we drove on to Metz to contemplate our personal family connection to that strange place and the three day weekend we were enjoying. I was feeling more motivated than ever to know if there was more to Walter and his wife Lucy Stone Terrill, the intrepid author and traveler, than what I’d gleaned so far from googling. I wondered if Lucy had descendants who might have her more-personal writings, and whether they’d tell me more about Walter or her in-laws, i.e. my own family. When I got home I dug a little deeper on Ancestry and discovered that Lucy was the hub of a family tree created by a woman named Susan Bugbee. Using the messaging feature on the app, I reached out to Susan a month after the November visit to France, and to my delight heard right back from her. This led to a lovely online correspondence, and unlocked a goldmine of information and insight.

Susan revealed that she was no relation to Lucy Stone Terrill, and that the Terrill family tree she had built on the Ancestry app was part of a much broader, years-long research project into Lucy. She had posted the tree and other research on the Ancestry site with the exact intent of attracting living relatives who could shed more light on her favorite subject. Susan, as it turned out, had worked for years at the University of San Diego, first as a graduate student, then an administrator–eventually in the registrar’s office–still ‘spending her lunch hours reading microfilm in the library,’ as she told me, frequently for the purpose of researching Lucy. We hit it off, as you can see from the warmth of our first email thread , and in our joy at having found each other, we quickly began exchanging materials and filling in gaps in each other’s research.

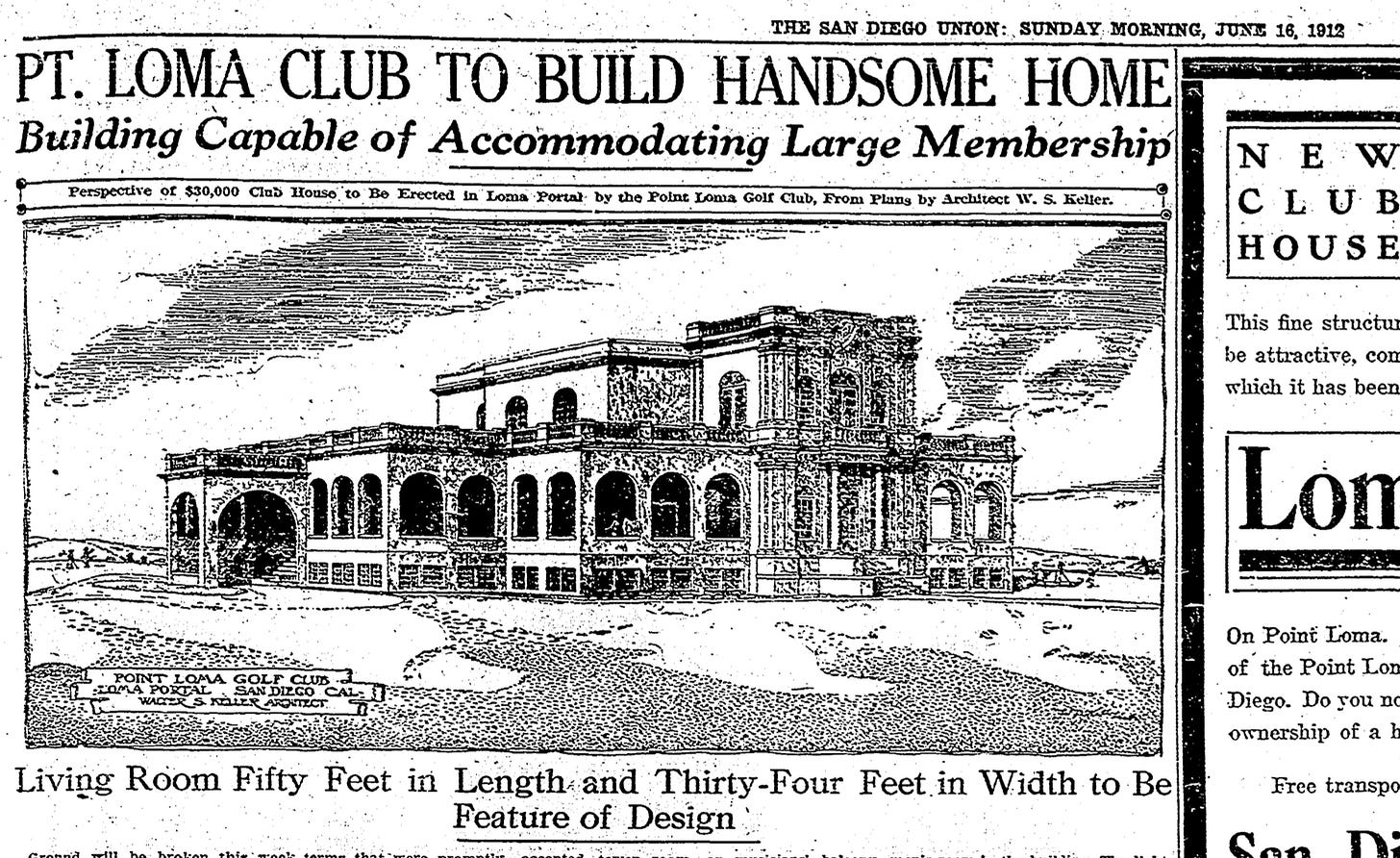

Among other mandates, it’s apparent that USD has a mission to study and preserve San Diego history, a directive clearly instilled in alumni like Susan. As a student in 1984, Susan had participated in a class project to catalog San Diego’s historically important architects, and revealed, to my surprise, that Walter Keller is one of them! Susan’s description of him as a famous architect shook me a little, as it replaced the romantic, tragic image (which I realized my mother and I had entirely invented) of him being part of the Lost Generation of WWI, that he had never had a chance to share his creative talents with the world, and so on. This was an entirely different person who chose to pause a successful career (and seemingly lovely marriage) to join the war effort against German aggression.

Of course in a way this revelation made it even harder to understand his choice. With apologies for my lack of patriotic instinct, I had to wonder how he gave all that up. WWI is often viewed through the lens of folly and waste, even for its victors, who squandered the peace dividend and other opportunities earned by Walter’s generation’s sacrifice. His decision to join the war effort was not uncommon among American men, but his brother-in-law, my great-grandfather Laurence Tanzer, for example, does not seem to have contemplated enlisting.

I wondered whether Walter ever felt any tinge of divided loyalty, given that all four of his grandparents were German. His father David had grown up in Idar-Oberstein, a (depleted) Saarland jewel mining town just 2 hours’ drive from where Walter served and died. Only a couple generations before, the family had decided to leave Germany forever, determining it had little left to offer them even after untold generations living there, compared to the promise of 1840’s America.

If he felt any particular affinity to his father’s homeland, perhaps he experienced it as a desire to save Europe— Germany included — from the Kaiser and his ilk. In the runup to the US joining WWI there had been 3 years of press about the ‘rape of Belgium,’ notably the dramatic German atrocities in Leuven (a quick drive from my current home), as well as everywhere else they marched. Those reports surely reached Walter and intruded on his newlywed bliss; witness this San Diego newspaper that happened to publish an elaborate map of the war front on the same day and page with the story of his wedding to Lucy.

Besides, he already counted himself as belonging to the US Military. This record I turned up indicates that he had been in the army 10 years earlier, apparently for just a year or so, from 1907-1908, when his profession was listed as ‘draftsman’. That past service was likely another spur to him re-enlisting, and meant that he would start this time as a captain. Entering with this rank and working as an engineer might also have given his wife and family hope that he would not be on the frontlines.

I had a second revelation that along with Walter’s age, I had missed another crucial clue in the watercolors (2nd): they were dated 1915! This meant they were from two years before the US entered the war, and 3 years before he went to Alsace. My cousin and fellow family archivist (though not a Keller but a Bunzl relation), Jim Blum, immediately recognized the Strasbourg cathedral steeple in one of the paintings, which made me laugh as I myself hadn’t clocked it despite several recent visits. I agreed it was almost certainly Strasbourg, and I spent a while puzzling over how Walter had painted that landmark since it was an hour and many miles behind enemy lines–before realizing: he had painted it THREE YEARS before being posted there.

In other words, he painted the Alsatian images while still living in California, perhaps from postcards or newspaper images. How often did he sit down and paint during his whirlwind San Diego years? Where have all those other paintings gone? Why did he paint images of the region he was destined to fight and die in? It couldn’t be a total coincidence that he had the idyllic Rhineland on his mind as he sat wishing that he and America could do more to bolster the war effort, against those bellicose nationalists driving his family’s fatherland toward its ruin.

The years before the war were a gilded age of development in San Diego. It was a new and modern city, with many prosperous families building mansions, country clubs, and multi-use high rises, many in cool new California styles with shades of Spanish colonial architecture and aesthetic links to the burgeoning Arts and Crafts movement. These beautiful, historic buildings were all catalogued –with Walter’s many contributions fully credited and documented, first thanks to USD’s 1984 undergraduate project, and then in a second study that Susan shared with me next, written four years later by a scholar named Richard Carrico: a full thesis entirely on the subject of Walter Keller and his place as one of San Diego’s ‘shadow architects.’

I can still hardly express my gratitude to Mr. Carrico, (and to Susan!) for these wonderful studies identifying and preserving Walter’s legacy. Along with Carrico’s excellent thesis came a rich bibliography that pointed me directly to a number of newspaper articles from the period describing or even displaying Walter’s designs.

The scholarly documentation undoubtedly contributed to the historic designation and preservation of the buildings themselves. Many are still standing, a legacy that Walter’s family had never known of till now. But now with the proper keys I’m as fascinated as any of these historians, and the material keeps on giving! For example this nomination of one of his houses for historic status goes into detail about Walter’s influences and even ties the building to his original reasons for coming to San Diego in 1909. I cannot wait to visit these buildings–our friend Leroy has moved to San Diego and my cousin Marian is not too far away in Pasadena with her family so we’ll get there before long. When we do I dearly hope Susan Bugbee will show us around.

Susan’s own research, sparked in part by her school’s study of Walter Keller, evolved in the years since into a lifelong and highly contagious fascination with Walter’s wife, Lucy Stone Terrill. This culminated in Susan writing a compelling and comprehensive monograph of Lucy in 2016, which I cannot recommend highly enough, dear reader.

With much more rudimentary internet access than we have now, Susan spent years locating many of Lucy’s writings and other documents, and collected them as she built her biography, as well as any supporting newspaper articles, of which she found many from San Diego alone. She sent letters and emails to archivists and librarians around the country–Lucy had lived in seemingly every corner–as well as connecting with Lucy’s living descendants (no children). Along the way she amassed an impressive paper archive, which she recently sent to me. I have digitized (or found online) most of her resources, and wherever possible I turned her footnotes into live links leading directly to the press articles and to Lucy’s wonderful short stories which though fictional, contain obvious biographical echoes and insights into Lucy’s real life.

Lucy grew up on among Wyoming ranchers, and many of her stories took place in that milieu, with strong male and female protagonists in equal measure, often falling in love while grappling over emotional and physical territory.

She lost her mother at an early age, as well as some of her inheritance, and was raised mostly by aunts and other relatives. A writer from the start, she supported herself as an author of excellent short stories filling the pages of the most popular magazines of the day. She tried a couple homes before settling into the burgeoning social and creative scene in San Diego. She joined a number of brainy ‘ladies’ clubs’ and was a featured speaker at their gatherings.

She met Walter in this society and it seems to have been a whirlwind romance, culminating in a 1914 trip to Portland, Oregon during which the couple married, inviting no friends from San Diego nor any of Walter’s (my) family. They came back to San Diego and were featured in a write-up about their quasi-elopement. One hopes that their brief marriage was blissful. Apparently a bit of an ‘it’ couple in the burgeoning San Diego society, those years were periodically chronicled by the San Diego Union, and Susan Bugbee’s biography of Lucy, which I can’t recommend highly enough, reveals some amazing details and insights about the city and country in that era, as well as the couple’s life together in the midst of it all.

But the building boom that characterized Walter’s San Diego career appears to have ended in 1916–perhaps coinciding with the famous ‘rainmaker’ floods that shook the local economy that year. Walter moved to Detroit to briefly work for a firm there, and then home to New York, where he almost immediately re-joined the Army and left his family again, this time leaving Lucy with them.

She stayed with his family in Mount Vernon, NY, specifically his sister Florence Keller Tanzer and her husband Laurence Tanzer, two figures much better known to our family, as they lived into the 1960’s, as did their daughter Peggy Tanzer Bunzl, my grandmother, who I never knew but my sisters remember, and Elly Tanzer Seidel, my great aunt who lived until 1980 with her husband Sam Seidel, both of whom I remember well.

When they took in Lucy Stone Terrill during the war years, Florence and Laurence had three girls under ten running around the house. Yes, there was a third sister, Alice Tanzer, who would die in 1919 during the Influenza pandemic. But when Lucy was living with the Tanzers, the house was apparently one of great joy and activity, a moment which Susan revealed to my amazement: Lucy had immortalized in writing! For My Country (1917) is a sweet satirical short story she wrote about just such a family caught up in the patriotic excitement of the early months of WW1.

Lucy’s fascinating biography continues after Walter’s death in 1918; thanks to Susan’s amazing monograph I learned that she chose to honor his memory through action, traveling to France and working with the YWCA to ease the suffering of refugees, POW’s and American vets after the armistice, part of a volunteer movement of war widows that led to Lucy being featured in a 2012 book on the subject.

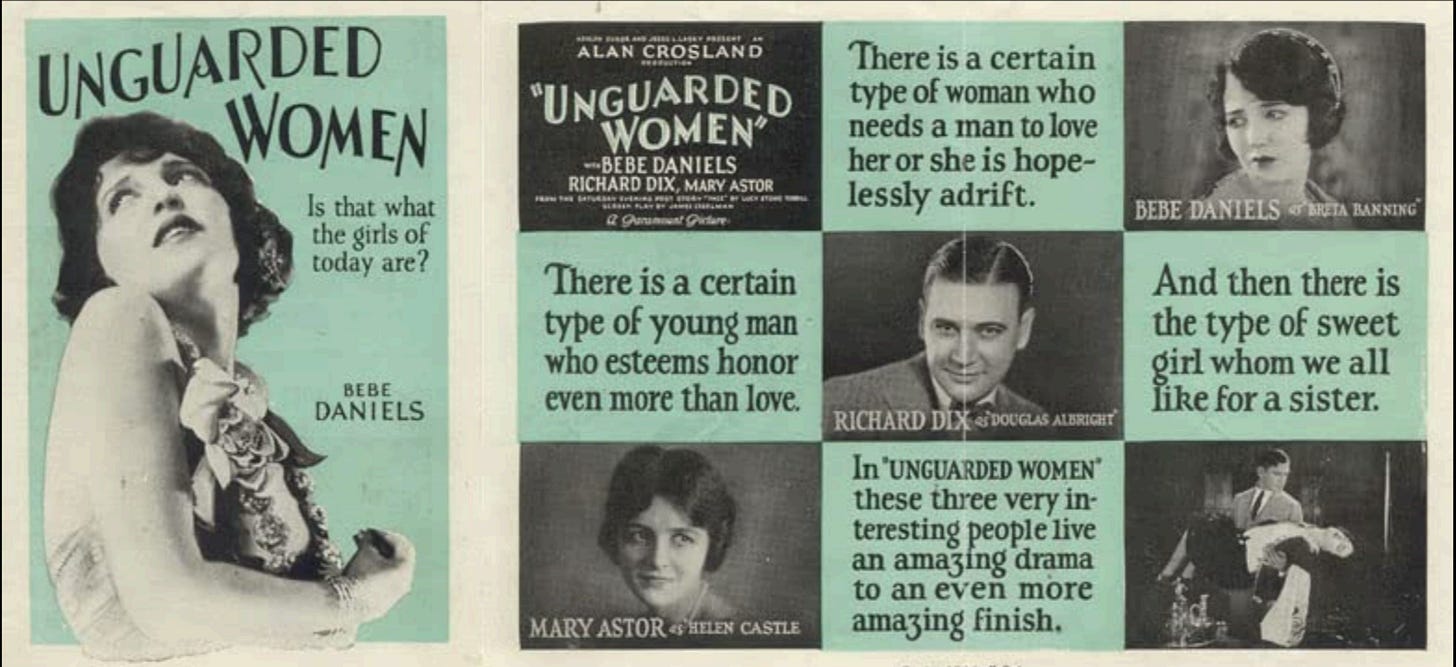

She then returned to San Diego, where she restarted her life as a teacher and continued to write and publish. But before long she left for an intrepid and extensive journey around Asia. Her postwar European and Asian travels clearly colored her 1924 short story Face. This features the characters of a young war widow and a veteran who meets her in Peking, both haunted by their losses in the French trenches. This was one of her biggest successes, and was adapted into a film called ‘Unguarded Women,’ a film sadly now lost except some very cool posters.

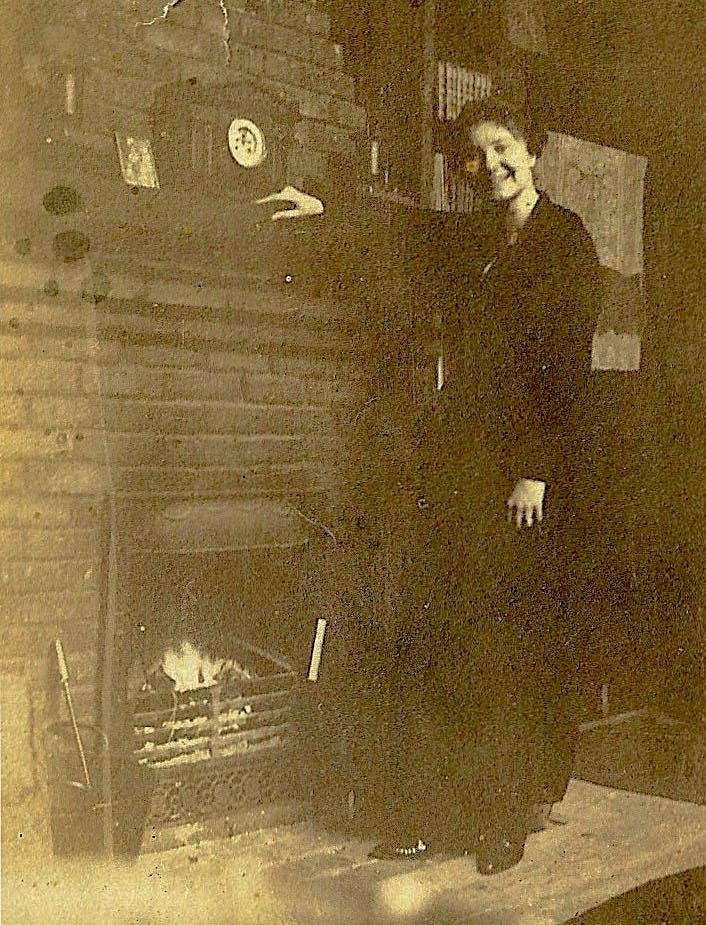

It was probably on her Asian travels that she met her second husband, a dashing Army doctor, with whom she settled in Sarasota, Florida, during the years that the Ringling family were building the city up. There she continued to write, build community and appear in the local press, so Susan was able to follow the trail nearly to Lucy’s final days. It seems she stayed in touch with my family as well. Her mother-in-law Clara Fink Keller was in the dedication of her one novel (listed among ‘my mothers’) and we have one Christmas card she wrote to her sister and brother in-law, Laurence and Florence, a photo of her smiling but still in black, which she’s inscribed ‘Foolish, but pleasant.’

The Kellers and Tanzers’ lives went on after Walter as well, of course. They’re surprisingly well documented, in fact, first because Laurence’s law career included such historic inflection points as founding the Citizens Union; developing worker protections after the Triangle Factory Fire and co-authoring the Charter of New York, some of which is documented in his professional memoir.

Both Laurence and Florence also wrote personal memoirs–Florence’s devotes a whole page to Walter and Lucy, with touching insights and anecdotes about both, including characterizations of Walter as sowing wild oats in the army ten years earlier, and in Texas as a rambling, gambling cowboy and rodeo circus rider. Meaning he moved away–much farther away from his family than any of his siblings– and went adventuring in an arguably somewhat self-destructive manner. From Texas he moved onto San Diego, a less ‘wild’ west but still a very undeveloped place rife with opportunity, which he obviously seized in the manner of a town founder of sorts. He also seized the day upon meeting Lucy Stone Terrill; their wedding seems like a rather impulsive elopement for people in their thirties, and it feels telling–though I’m not sure of what– that nobody from his family attended.

What had his relationships been like with the family he serially left behind in New York? His German father who died at 55? His sister Florence who took in his young wife Lucy? When opportunities began to wane in San Diego, Walter first tried to move to Detroit and rebuild his career there, but it wasn’t long before he and Lucy were back among his family in New York, though he left again almost as quickly, attracted to sign up as an officer engineer in the war.

The memoirs touch much more briefly on the passing one year later of Alice Tanzer, the couple’s angelic third child who died of influenza in 1919 at age eight. This devastating loss must have compounded the family’s loss of Walter just a few months earlier. A tragedy even sadder than Walter’s, too sad to talk about I suppose, but that lives on in a large life-size oil painting they had commissioned after she died, which ended up at my aunt Alice’s house, where even casual viewers without the background tend to agree it’s a haunted portrait.

Hard to know why Walter had headed west, and moved so much farther away than the other siblings, but Florence’s description seems very warm, and he appears to be enjoying his siblings in the group shots we have of him before going off to training. His mother Clara seems less happy in those photos from just before he shipped out (nor does Lucy—both are surely feeling the risks facing him). Walter seems by far the most jovial; given his rough riding past, he may well be looking forward to breaking away and taking on the war as yet another adventure.

Outliving both a son and a granddaughter, Clara must have taken the family’s double loss as hard or harder than anyone. It seems from Lucy Stone Terrill’s dedication to her in the novel that Clara was very kind and welcoming to Lucy, and Florence does not indicate any judgement against Lucy for having remarried, though the evidence so far indicates they lost touch after Lucy moved to Sarasota.

Lucy Stone Terrlll was a survivor, an unstoppable creative force who pointedly responded to Walter’s loss first with direct action—volunteering in post-war Europe —and then by rebuilding her life with new creative output, a new marriage and a new community in Sarasota, where she remained as charismatic, prolific and engaged as ever. If she continued to think about Walter, if she held onto keepsakes or documents (his or her journals, or in a perfect world, more of his artwork!), Susan was unable to track any of them down in her tireless outreach to archivists around the country or even Susan’s nephew in Sarasota, who sent her a kind response in 2016. He offered a few more great details, like Lucy working with the Ringling family on the beautification of Sarasota, and confirmed he has a box of her effects, but no journals. I look forward to reaching out to Lucy’s family again once I have this memoir in shape; hope springs eternal that something in here will spark more revelations!

I have sometimes wondered what kind of permanent damage that horrible fall and winter of 1918-1919 might have done to my family. Was the family paralyzed by mourning Walter and then Alice? Did it make the house permanently less joyful? Make Laurence throw himself more into his soon-to-be-illustrious career? Make Laurence and Florence more loving or indulgent? Did it define the way the family spoke about death, grief, loss? Did it make Florence even more of a caretaker, as when she and Laurence took in her other brother Joe and his two sons a few years later and helped raise her nephews after their mother Edna died?

Did the losses continue to mark the family when Peggy had her two daughters in the 1930’s (my mother Lucy and her sister Alice)? Might the old wounds and bonds from this time have contributed to Peggy’s decision to live with her parents every summer in their house in Rye? Florence’s boundless capacity for nurturing continued when my mother had my sisters, particularly Liz who remembers living with them in the early sixties after Lucy (Bunzl Mallan) separated from her first husband Augie. It may for the best that Florence and Laurence did not live to see another daughter die–my grandmother Peggy from Cancer, at 62; but they only pre-deceased her by a few years, and were pillars of the family till then.

As rich a discovery as this has been, studying the facts of Walter and Lucy’s lives, getting to know them after a fashion, has clearly raised more new questions than it’s answered. It is unheard of for most people at the turn of the twentieth century to have had the facts of their lives recorded in this way (and certainly for my ancestors, try though they might to live on in their own memoirs). The couple was immortalized in the local press, in the stories Lucy wrote and in the buildings Walter built. These public aspects of their life call to mind what social media archives might give a researcher in the year 2125 for just about any of us. Those archives may tell a public-facing version of our story but still leave an incomplete picture, with any curious descendant still be seeking threads, patterns and truth between the lines that might explain how the family got from here to there, how we became who we are.

In the case of a family experiencing an early death, not only Walter’s but the nearly unspeakable loss of Alice Tanzer just months later, I suppose the fundamental question is how the lives in Peggy’s generation, then Lucy and Alice Bunzl’s, then my own might have been different if Alice Tanzer had survived her influenza; if Walter Keller hadn’t died just before the armistice; if the extraordinary Lucy Stone Terrill had remained part of our family. In this way the questions have only multiplied and deepened as I’ve learned more of the facts. And still I’m grateful for all that was revealed when I met Susan Bugbee, and she so generously shared the story of Walter Keller and Lucy Stone Terrill.

Annotated List of articles supporting Walter Keller’s biography, compiled by Susan Bugbee, complemented by Richard Carrico, and sourced, linked and annotated by Tom Mallan.

RESOURCES:

Annotated List of articles supporting Lucy Stone Terril’s biography, compiled by Susan Bugbee and sourced and linked by Tom Mallan.

Bibliography of all known writings by Lucy Stone Terrill, compiled by Susan Bugbee and sourced and linked by Tom Mallan.

A couple photo albums including relevant material from the period:

SPECIAL THANKS:

—to any kind souls who read this. I would be grateful for your feedback, as I am really just beginning as a writer.

—to all who helped create this memoir, including Richard Carrico and most especially Susan Bugbee. I may well update it as more facts and materials come to light—if you, dear reader, know any other facts, or have any other materials related to these subjects, please: be in touch!

Tom: Great job. Touching, informative, and personal.

Richard Carrico